The Turn End Trust organises an annual lecture on architecture and landscape. This year’s lecture was given by Dr. Alan Powers, titled ‘Modern Houses: The Smooth and the Hairy’. Alan writes and talks on art, design and architecture, with a particular knowledge of private houses of the 20th Century. Here, Jackie Hunt, Turn End’s gardener recalls the lecture.

On a blissfully warm early September afternoon we were treated to a fascinating lecture by Dr. Alan Powers on Modern houses, followed by tea and cakes in Turn End’s garden. The title was intriguing – what could he mean by smooth or hairy houses?

Alan began by introducing the dichotomy of the Apollonian and Dionysian, which are philosophical and literary concepts from ancient Greek mythology. Apollo and Dionysus are both sons of Zeus. Apollo is the god of rational thinking and order, appealing to prudence and purity. On the other hand, Dionysus is the god of the irrationality and chaos, appealing to emotions and instincts. These characteristics have parallels with smooth and hairy, the latter evoking less sophistication, but also closeness to nature, authenticity and honesty. Smooth can also have negative implications – lack of trust and hollowness.

Modern house design can be seen as see-sawing between these two positions. For example, after the First World War there becomes a recognisable ‘formula’ for Modern houses of the smooth or Apollonian ethos, epitomised by Villa Savoye in Poissy, France. Designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret and built between 1928 and 1931 using reinforced concrete, it exemplifies Le Corbusier’s idea of ‘the house as a machine for living’. With upper floors supported by piers, the house is so smooth it appears to float above the ground.

Villa Tugendhat by Ludwig Mies Van de Rohe (Photo: Villa Tugendhat / Brno City Museum)

Mies van de Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat, Brno, Czech Republic became an icon of modern architecture in Europe, built of reinforced concrete between 1928 and 1930 for Fritz Tugendhat and his wife Grete. Without paintings or decorative items some criticised Mies’ ‘less is more’ ethos as too machine-like. However, Grete defended the design, saying how uplifting the house was for living. The villa also acts as a frame for the magnificent views, the architect making the natural and hairy landscape an integral part of the interior.

As the 1930s progress a contrast emerges. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, or the Kaufmann Residence, 1935, in rural southwestern Pennsylvania, exemplifies the hairy. Wright rejected city living and believed one should go back to nature. Built of rough stone, it is deeply embedded in its environment. Alvar Aalto was also much inspired by this for his Villa Mairea, 1938-9, which could be called ‘polite’ hairy. Its sinuous form and interior of wooden poles evoke a forest, providing narrative and a journey rather than machine-like living.

Le Corbusier also departed from his principles of standardisation and the machine aesthetic and turned more to rural inspiration. He took retreat in the Jura mountains one winter, residing in a particularly hairy farmhouse with a dominant central fireplace and large chimney, from which he took much inspiration. His Villa de Madame H. de Mandrot, Le Pradet, France, 1929 is built of rough stone, whilst Maison de Week-end, La Celle-Saint-Cloud, France, 1934, includes a central, dominant rough brick fireplace and even has a grass roof. Le Corbusier had studied Ruskin, who attacked smoothness and falsification, believing materials could be poor as long as they were honest.

Even Walther Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School, known as the ‘Silver Prince’ and exponent of the Apollonian made a transition in style with his timber-clad The Wood House, Shipbourne, Kent, designed with Edwin Maxwell Fry, 1936.

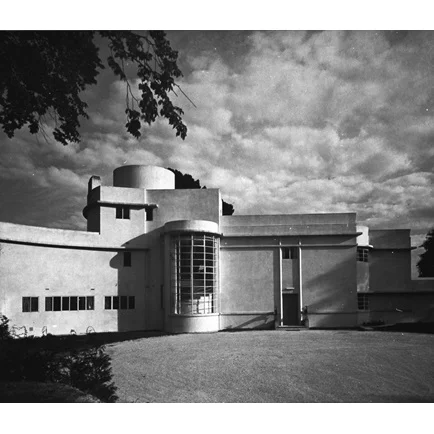

Joldwynds by Oliver Hill

Some architects could be both smooth and hairy almost at the same time. Oliver Hill designed two houses in the village of Holmbury St Mary. Surrey. Woodhouse Copse, 1928, is a thatched, brick built and weatherboarded cottage that contrasts with his smooth, white, flat roofed Joldwynds, 1932. In Jordans, Buckinghamshire, Colin Crickmay designed white-painted Twitchell’s End for his Modernist-loving clients, but a second nearby commission is ‘traditional’, with a steep pitched roof and a catslide to the rear. In later life Crickmay explained “I came to the conclusion quite early on that a flat roof was not really suitable for this country”.

After the second World War smoothness returned to architecture, such as the Royal Festival Hall, 1951, and the first glass and steel house in the UK, by Michael Newberry at Panshanger, Surrey, 1962. Alongside this a new style was emerging. Le Corbusier designed a pair of houses, Maison Jaoul in Paris, 1954. Their rugged, hairy aesthestic of unpainted cast concrete and roughly detailed brickwork become an influence on ‘New Brutalism’, such as the Hayward Gallery and the work of Alison and Peter Smithson, known for their stripped back designs, rough finishes and deliberate lack of refinement, such as Sugden House, Watford, 1956.

The Wedgwood House by Aldington and Craig (Photo: James Davies)

Where does the work of Aldington, Craig and Collinge fit into this picture? Their work is sometimes described as ‘Romantic Pragmatism’, where place, materials and relation to the individual are important. Many of their houses are textural and romantic but some exhibit smoothness and regularity, such as the steel framed Wedgwood House (Ketelfield) in Essex. All are informed by and created for people and how they live their lives. Turn End, Peter Aldington’sown home, is sympathetic to Haddenham’s special quality with its walled courtyards and demonstrates an indistinguishable relationship between inside and out. As Juhani Pallasmaa comments in his 1996 book, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, perhaps Modernism has not become popular because it focusses on intellect and the optic – what can be seen, rather than the haptic – the quality of sound and scent, what can be touched, felt, or even imagined as you look at the texture of a surface. Turn End may be a little hairy, but it certainly awakes the senses.

Turn End, Haddenham by Peter Aldington (Photo: Richard Bryant)

With many thanks to Dr. Alan Powers https://twitter.com/alanpowers99?lang=en

Afternoon tea in Turn End garden (Photo: Peter Aldington)